"The Compiègne Town-hall" by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1876

"In black relief on a gilt ground, Louis XII rides upon a pacing horse, with hand on hip and head thrown back. There is royal arrogance in every line of him."

In An Inland Voyage, Robert Louis Stevenson recounts a canoe trip he and a friend made along canals and the Oise River in Belgium and France in 1876.

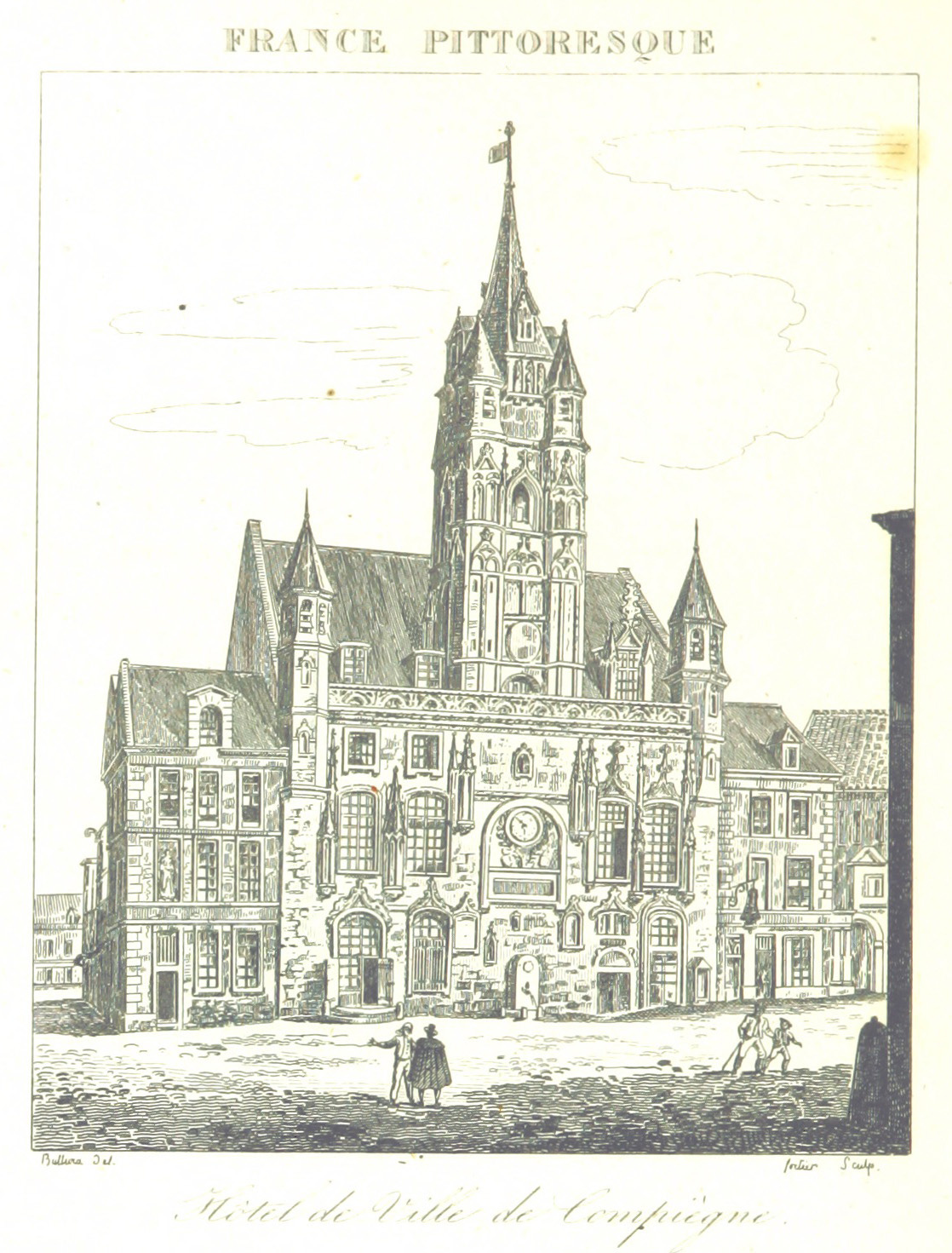

My great delight in Compiègne was the town-hall. I doted upon the town-hall. It is a monument of Gothic insecurity, all turreted, and gargoyled, and slashed, and bedizened with half a score of architectural fancies. Some of the niches are gilt and painted; and in a great square panel in the centre, in black relief on a gilt ground, Louis XII rides upon a pacing horse, with hand on hip and head thrown back. There is royal arrogance in every line of him; the stirruped foot projects insolently from the frame; the eye is hard and proud; the very horse seems to be treading with gratification over prostrate serfs, and to have the breath of the trumpet in his nostrils. So rides forever, on the front of the town-hall, the good king Louis XII, the father of his people.

Over the king’s head, in the tall centre turret, appears the dial of a clock; and high above that, three little mechanical figures, each one with a hammer in his hand, whose business it is to chime out the hours and halves and quarters for the burgesses of Compiègne. The centre figure has a gilt breast-plate; the two others wear gilt trunk-hose; and they all three have elegant, flapping hats like cavaliers. As the quarter approaches, they turn their heads and look knowingly one to the other; and then, kling go the three hammers on three little bells below. The hour follows, deep and sonorous, from the interior of the tower; and the gilded gentlemen rest from their labours with contentment.

I had a great deal of healthy pleasure from their manœuvres, and took good care to miss as few performances as possible; and I found that even the Cigarette [Stevenson’s companion], while he pretended to despise my enthusiasm, was more or less a devotee himself. There is something highly absurd in the exposition of such toys to the outrages of winter on a housetop. They would be more in keeping in a glass case before a Nürnberg clock. Above all, at night, when the children are abed, and even grown people are snoring under quilts, does it not seem impertinent to leave these ginger-bread figures winking and tinkling to the stars and the rolling moon? The gargoyles may fitly enough twist their ape-like heads; fitly enough may the potentate bestride his charger, like a centurion in an old German print of the Via Dolorosa; but the toys should be put away in a box among some cotton, until the sun rises, and the children are abroad again to be amused.

From An Inland Voyage by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1878, available on Amazon*

Classic Travel Tales on Facebook

More travel stories from Robert Louis Stevenson:

Robert Louis Stevenson’s story “Lost in the Dark” from Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (1879)

*As an Amazon Associate we earn a bit from qualifying Amazon purchases.

Image: “Hôtel de ville de Compiègne,” from France Pittoresque by Jean Abel Hugo, 1835, The British Library Collection, public domain.