"Punch and Judy" by Mark Twain, 1878-1879

"The tourists were all agreed upon one thing—one must expect to be cheated at every turn by the Italians."

For several weeks I had been culling all the information I could about Italy, from tourists. The tourists were all agreed upon one thing—one must expect to be cheated at every turn by the Italians. I took an evening walk in Turin, and presently came across a little Punch and Judy show in one of the great squares. Twelve or fifteen people constituted the audience. This miniature theater was not much bigger than a man’s coffin stood on end; the upper part was open and displayed a tinseled parlor—a good-sized handkerchief would have answered for a drop-curtain; the footlights consisted of a couple of candle-ends an inch long; various manikins the size of dolls appeared on the stage and made long speeches at each other, gesticulating a good deal, and they generally had a fight before they got through. They were worked by strings from above, and the illusion was not perfect, for one saw not only the strings but the brawny hand that manipulated them—and the actors and actresses all talked in the same voice, too. The audience stood in front of the theater, and seemed to enjoy the performance heartily.

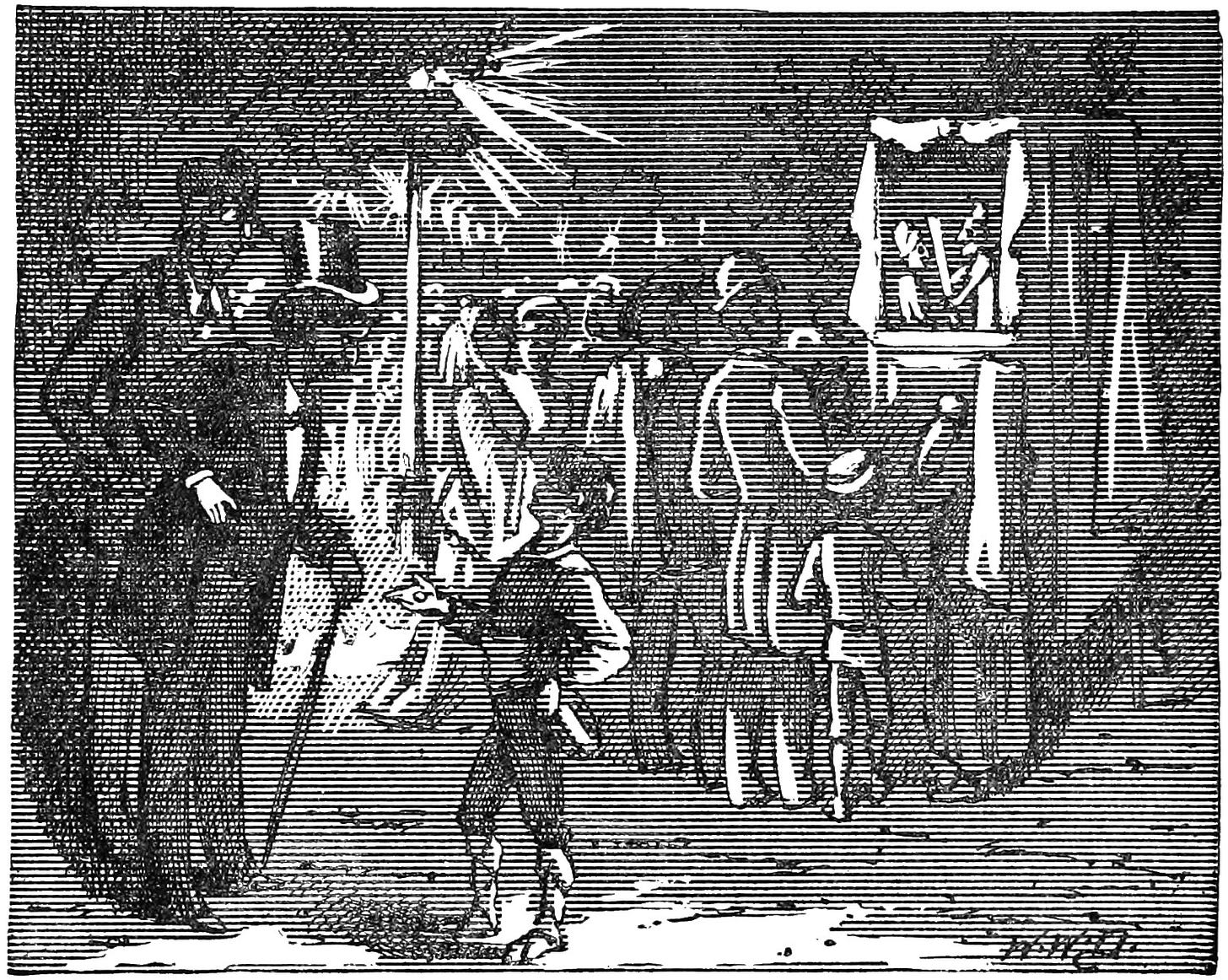

When the play was done, a youth in his shirt-sleeves started around with a small copper saucer to make a collection. I did not know how much to put in, but thought I would be guided by my predecessors. Unluckily, I only had two of these, and they did not help me much because they did not put in anything. I had no Italian money, so I put in a small Swiss coin worth about ten cents. The youth finished his collection trip and emptied the result on the stage; he had some very animated talk with the concealed manager, then he came working his way through the little crowd—seeking me, I thought. I had a mind to slip away, but concluded I wouldn’t; I would stand my ground, and confront the villainy, whatever it was. The youth stood before me and held up that Swiss coin, sure enough, and said something. I did not understand him, but I judged he was requiring Italian money of me. The crowd gathered close, to listen. I was irritated, and said—in English, of course:

“I know it’s Swiss, but you’ll take that or none. I haven’t any other.”

He tried to put the coin in my hand, and spoke again. I drew my hand away, and said:

“No, sir. I know all about you people. You can’t play any of your fraudful tricks on me. If there is a discount on that coin, I am sorry, but I am not going to make it good. I noticed that some of the audience didn’t pay you anything at all. You let them go, without a word, but you come after me because you think I’m a stranger and will put up with an extortion rather than have a scene. But you are mistaken this time—you’ll take that Swiss money or none.”

The youth stood there with the coin in his fingers, nonplused and bewildered; of course he had not understood a word. An English-speaking Italian spoke up, now, and said:

“You are misunderstanding the boy. He does not mean any harm. He did not suppose you gave him so much money purposely, so he hurried back to return you the coin lest you might get away before you discovered your mistake. Take it, and give him a penny—that will make everything smooth again.”

I probably blushed, then, for there was occasion. Through the interpreter I begged the boy’s pardon, but I nobly refused to take back the ten cents. I said I was accustomed to squandering large sums in that way—it was the kind of person I was. Then I retired to make a note to the effect that in Italy persons connected with the drama do not cheat.

From A Tramp Abroad by Mark Twain, 1880, available on Amazon*

Classic Travel Tales on Facebook

More travel stories from Mark Twain:

Mark Twain’s story “A Sleepless Night” from A Tramp Abroad (1880)

Mark Twain’s story “An Awkward Encounter” from A Tramp Abroad (1880)

Mark Twain’s story “By Train in India” from Following the Equator (1897)

Mark Twain’s story “Journey to Benares” from Following the Equator (1897)

Mark Twain’s story “Tarantulas on the Loose” from Roughing It (1872)

Mark Twain’s story “Lost in a Blizzard” from Roughing It (1872)

Mark Twain’s story “A Disturbing Incident” from Following the Equator (1897)

Mark Twain’s story “Athens by Stealth” from The Innocents Abroad (1869)

Mark Twain’s story “Carson City 1861” from Roughing It (1872)

Mark Twain’s story “Lake Tahoe” from Roughing It (1872)

Mark Twain’s story “An Archangel” from Life on the Mississippi (1883)

*As an Amazon Associate we earn a bit from qualifying Amazon purchases.

Image: “You’ll Take That or None” by William Wallace Denslow, from the first edition of A Tramp Abroad by Mark Twain, 1880, public domain.