"The Tombs, New York City" by Charles Dickens, 1842

"For what offence can that lonely child, of ten or twelve years old, be shut up here? Oh! that boy? He is the son of the prisoner we saw just now; is a witness against his father."

During Charles Dickens’s 1842 visit to the United States, described in his book American Notes, he visits New York City’s notorious prison, The Tombs.

What is this dismal-fronted pile of bastard Egyptian, like an enchanter’s palace in a melodrama!—a famous prison, called The Tombs. Shall we go in?

So. A long, narrow, lofty building, stove-heated as usual, with four galleries, one above the other, going round it, and communicating by stairs. Between the two sides of each gallery, and in its centre, a bridge, for the greater convenience of crossing. On each of these bridges sits a man: dozing or reading, or talking to an idle companion. On each tier, are two opposite rows of small iron doors. They look like furnace-doors, but are cold and black, as though the fires within had all gone out. Some two or three are open, and women, with drooping heads bent down, are talking to the inmates. The whole is lighted by a skylight, but it is fast closed; and from the roof there dangle, limp and drooping, two useless windsails.

A man with keys appears, to show us round. A good-looking fellow, and, in his way, civil and obliging.

“Are those black doors the cells?”

“Yes.”

“Are they all full?”

“Well, they’re pretty nigh full, and that’s a fact, and no two ways about it.”

“Those at the bottom are unwholesome, surely?”

“Why, we do only put coloured people in ’em. That’s the truth.”

“When do the prisoners take exercise?”

“Well, they do without it pretty much.”

“Do they never walk in the yard?”

“Considerable seldom.”

“Sometimes, I suppose?”

“Well, it’s rare they do. They keep pretty bright without it.”

“But suppose a man were here for a twelvemonth. I know this is only a prison for criminals who are charged with grave offences, while they are awaiting their trial, or under remand, but the law here affords criminals many means of delay. What with motions for new trials, and in arrest of judgment, and what not, a prisoner might be here for twelve months, I take it, might he not?”

“Well, I guess he might.”

“Do you mean to say that in all that time he would never come out at that little iron door, for exercise?”

“He might walk some, perhaps—not much.”

“Will you open one of the doors?”

“All, if you like.”

The fastenings jar and rattle, and one of the doors turns slowly on its hinges. Let us look in. A small bare cell, into which the light enters through a high chink in the wall. There is a rude means of washing, a table, and a bedstead. Upon the latter, sits a man of sixty; reading. He looks up for a moment; gives an impatient dogged shake; and fixes his eyes upon his book again. As we withdraw our heads, the door closes on him, and is fastened as before. This man has murdered his wife, and will probably be hanged.

“How long has he been here?”

“A month.”

“When will he be tried?”

“Next term.”

“When is that?”

“Next month.”

“In England, if a man be under sentence of death, even he has air and exercise at certain periods of the day.”

“Possible?”

With what stupendous and untranslatable coolness he says this, and how loungingly he leads on to the women’s side: making, as he goes, a kind of iron castanet of the key and the stair-rail!

Each cell door on this side has a square aperture in it. Some of the women peep anxiously through it at the sound of footsteps; others shrink away in shame.—For what offence can that lonely child, of ten or twelve years old, be shut up here? Oh! that boy? He is the son of the prisoner we saw just now; is a witness against his father; and is detained here for safe keeping, until the trial; that’s all.

But it is a dreadful place for the child to pass the long days and nights in. This is rather hard treatment for a young witness, is it not?—What says our conductor?

“Well, it an’t a very rowdy life, and that’s a fact!”

Again he clinks his metal castanet, and leads us leisurely away. I have a question to ask him as we go.

“Pray, why do they call this place The Tombs?”

“Well, it’s the cant name.”

“I know it is. Why?”

“Some suicides happened here, when it was first built. I expect it come about from that.”

“I saw just now, that that man’s clothes were scattered about the floor of his cell. Don’t you oblige the prisoners to be orderly, and put such things away?”

“Where should they put ’em?”

“Not on the ground surely. What do you say to hanging them up?”

He stops and looks round to emphasise his answer:

“Why, I say that’s just it. When they had hooks they would hang themselves, so they’re taken out of every cell, and there’s only the marks left where they used to be!”

The prison-yard in which he pauses now has been the scene of terrible performances. Into this narrow, grave-like place, men are brought out to die. The wretched creature stands beneath the gibbet on the ground; the rope about his neck; and when the sign is given, a weight at its other end comes running down, and swings him up into the air—a corpse.

The law requires that there be present at this dismal spectacle the judge, the jury, and citizens to the amount of twenty-five. From the community it is hidden. To the dissolute and bad, the thing remains a frightful mystery. Between the criminal and them, the prison-wall is interposed as a thick gloomy veil. It is the curtain to his bed of death, his winding-sheet, and grave. From him it shuts out life, and all the motives to unrepenting hardihood in that last hour, which its mere sight and presence is often all-sufficient to sustain. There are no bold eyes to make him bold; no ruffians to uphold a ruffian’s name before. All beyond the pitiless stone wall is unknown space.

From American Notes by Charles Dickens, 1842, available on Amazon*

Classic Travel Tales on Facebook

More from Charles Dickens’s American Notes

*As an Amazon Associate we earn a bit from qualifying purchases.

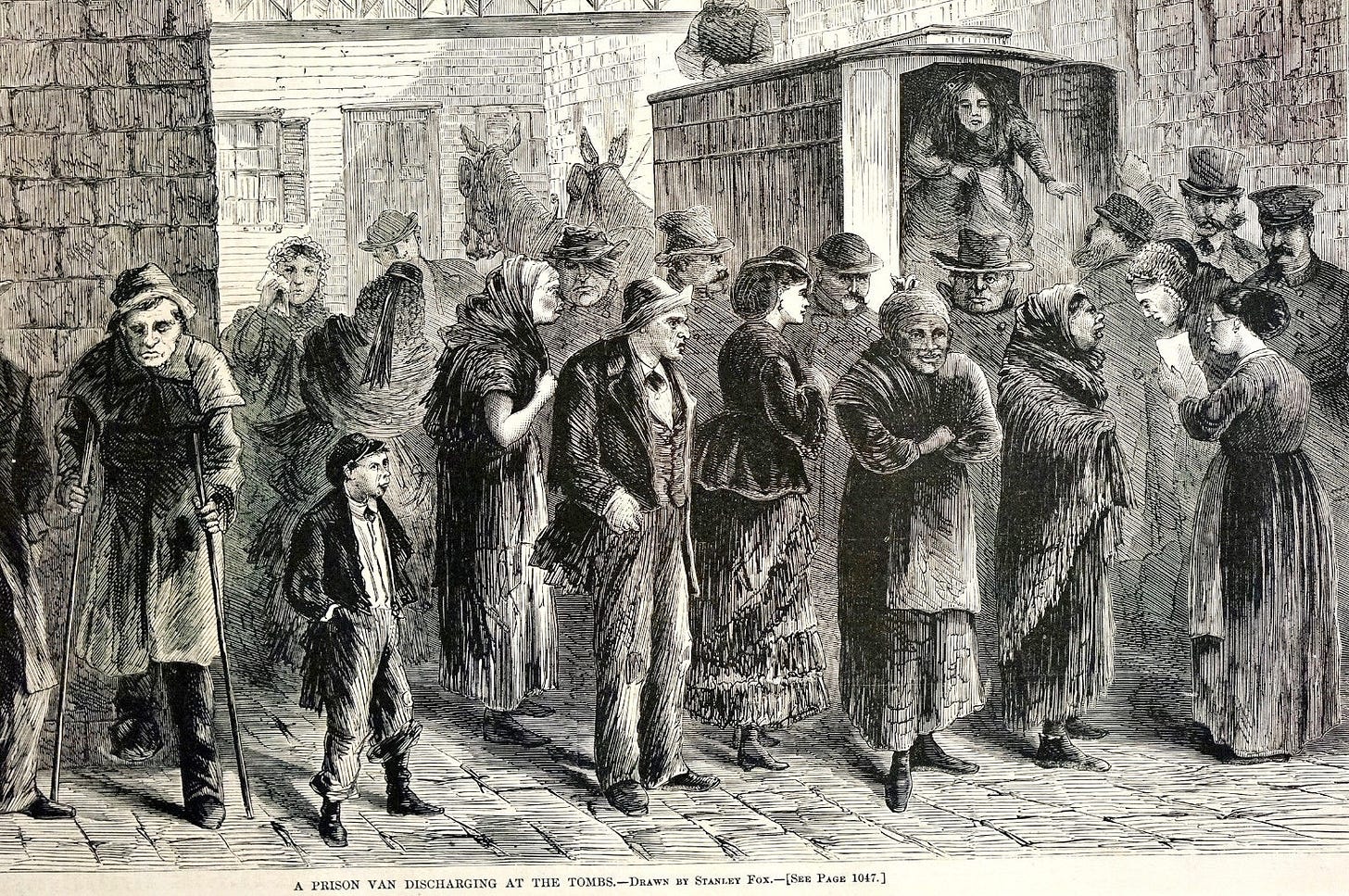

Image: “A Prison Van Discharging at the Tombs” by Stanley Fox, Harper's Weekly, 1871, public domain.